A landmark analysis published in 2022 found that the key reasons for the large decline in new infections in South Africa were antiretroviral treatment (since it makes people non-infectious) and the use of condoms.

Priscila Zambotto/Getty Images

Eight million people living with HIV. Just over 6 million on treatment. Behind these big numbers lurk a universe of fascinating epidemiological dynamics.In this special briefing,Spotlight editor Marcus Low unpacks what we know about the state of HIV in South Africa. This is part 3 of 3.In Part 1 of this Spotlight special briefing,we looked at some of the big picture dynamics of HIV in South Africa,and in Part 2,we considered some of the vulnerabilities of our HIV programme.

Now,in Part 3,we zoom into some nuances relating to HIV prevention,the epidemic in different provinces,gender disparities,and HIV in kids – after which we conclude this special briefing with our take on where all this data suggests we should be focussing next in South Africa’s HIV response.

Prevention problems

A landmark analysis published in 2022 found that the key reasons for the large decline in new infections in South Africa were antiretroviral treatment (since it makes people non-infectious) and the use of condoms.

ADVERTISEMENT

Voluntary medical male circumcision also contributed to reduced infections,more so for men,but also indirectly for women.

To some extent,all of these interventions are threatened by the recent aid cuts. Even prior to the cuts there were concerns that both condom distribution and usage has declined. Incidentally,the provision of condoms is probably the area of HIV prevention that has been impacted least by the aid cuts.

Last year,we reported extensively on injections that can provide HIV-negative people with six months of protection against HIV per shot. There are big unanswered questions about when these injections will become available and at what price,but experts have described it as a potential game-changer.

Spotlight/Supplied

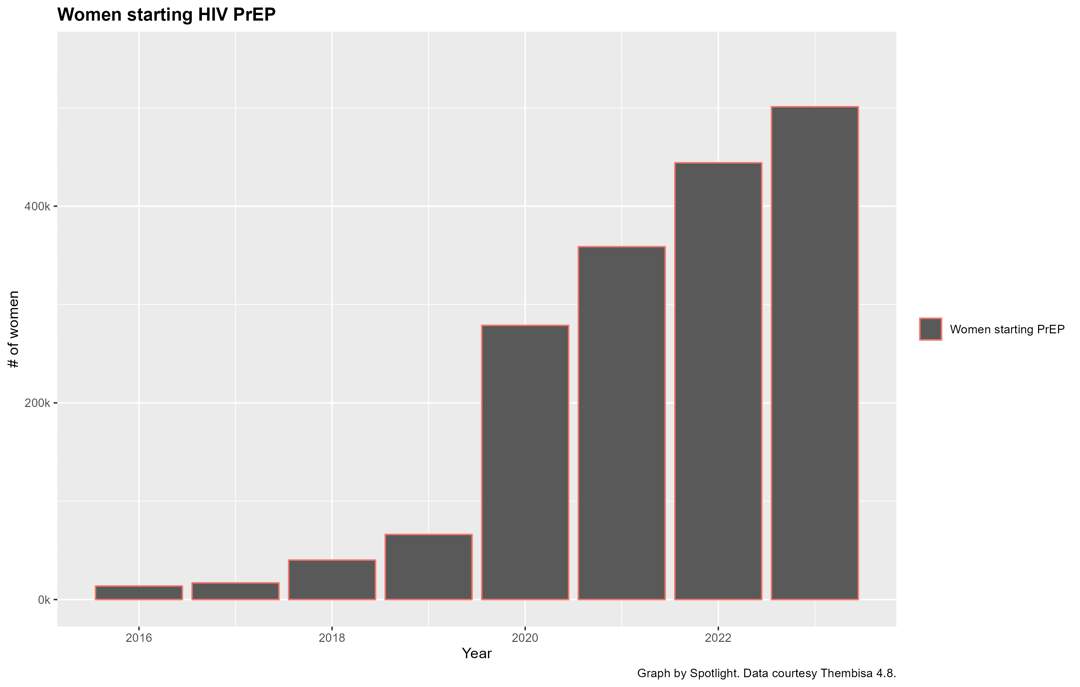

In the meantime,daily antiretroviral tablets that prevent HIV infection have already been rolled out in the public healthcare system over the last five or so years. The numbers here are tricky to parse since many people start taking the pills and then stop.

ADVERTISEMENT

For example,while 501 000 women started taking the pills from mid-2023 to mid-2024,less than half that number were still taking the tablets in mid-2024 – keep this in mind when considering the above graph.

Even so,there has clearly been a dramatic increase in women using HIV prevention pills in recent years.

How provinces compare

In South Africa,the health system,and most of the HIV programme for that matter,is run by provincial health departments.

Apart from demographics differing massively between the country’s nine provinces,the capabilities of their health departments also varies. It is thus no surprise that the HIV numbers look very different in different provinces.

Part of the difference between provinces is determined by things health departments can do little about,for instance the Eastern Cape quite simply is a more rural province than Gauteng.

On the other hand,some provincial departments have been chronically dysfunctional for decades which has no doubt impacted their HIV numbers.

Spotlight/Supplied

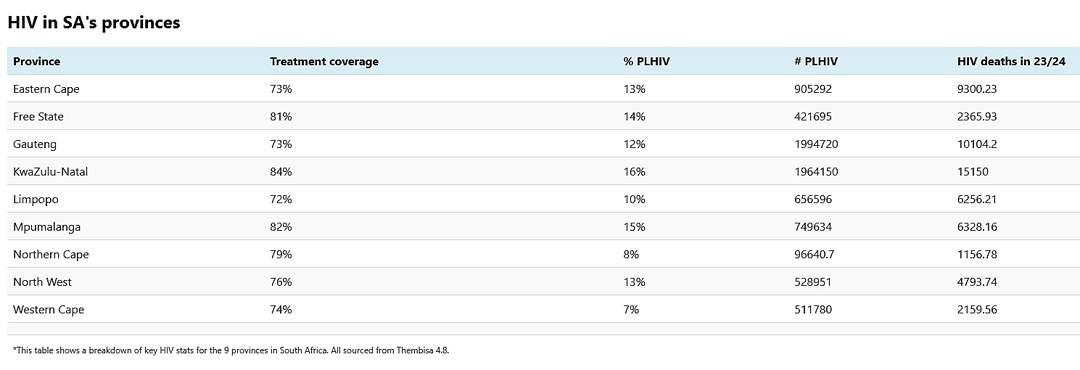

Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) are comfortably the country’s largest provinces by population,and it is thus no surprise that together they account for over 60% of all the country’s HIV cases.

But apart from their absolute numbers,they also have particularly high HIV prevalence – roughly 16% of people in KZN are living with HIV,compared to 7% in the Western Cape.

In terms of treatment coverage,the three worst performing provinces are the Eastern Cape,Gauteng,and Limpopo – all at around 73%. At 74%,the Western Cape is not much better. KZN leads the pack with 84%.

We focus on treatment coverage here since we consider it the single number that tells us most about how well a province is doing.

Maybe the most important contrast here is that between KZN and Gauteng. Both provinces have just under two million people living with HIV.

ADVERTISEMENT

Conventional wisdom would have it that delivering treatment would be harder in a more rural province like KZN,yet treatment coverage in KZN is more than ten percentage points higher than it is in Gauteng.

It is worth noting though that estimated HIV-related deaths are nevertheless higher in KZN than in Gauteng – possible explanations include much higher TB rates in KZN and worse socio-economic conditions.

Differences between men and women

Spotlight/Supplied

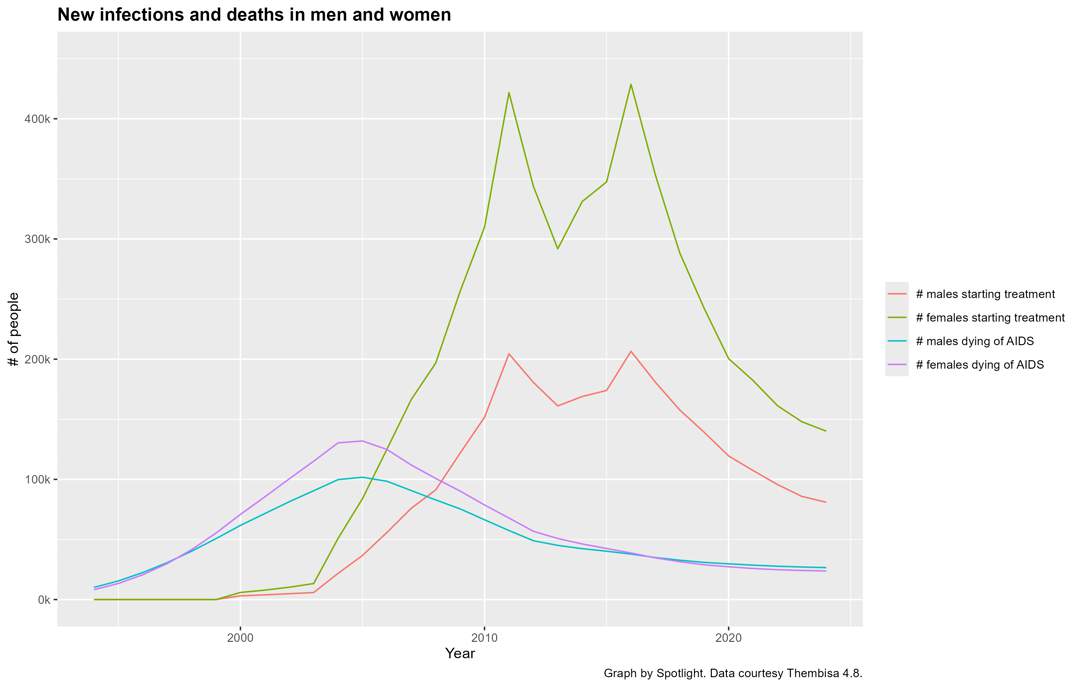

One of the most striking aspects about HIV in South Africa is that almost double as many women as men are living with the virus – 5.2 million versus 2.6 million in 2024. The reasons for this are not entirely clear but it is likely due to a combination of biology and social factors that determine who has sex with who.

Given these numbers,one might expect that many more women would be dying of HIV-related causes than men,but that is not what is happening. In fact,in 2023/2024,27 100 men died of HIV-related causes compared to 24 200 women.

Men are thus less likely to contract HIV than women,but once they have the virus in their bodies,they are on average much more likely to die of it than women. The numbers suggest that this is at least in part because men are both less likely than women to get tested for HIV and to take treatment once diagnosed.

The kids are not quite all right

Spotlight/Supplied

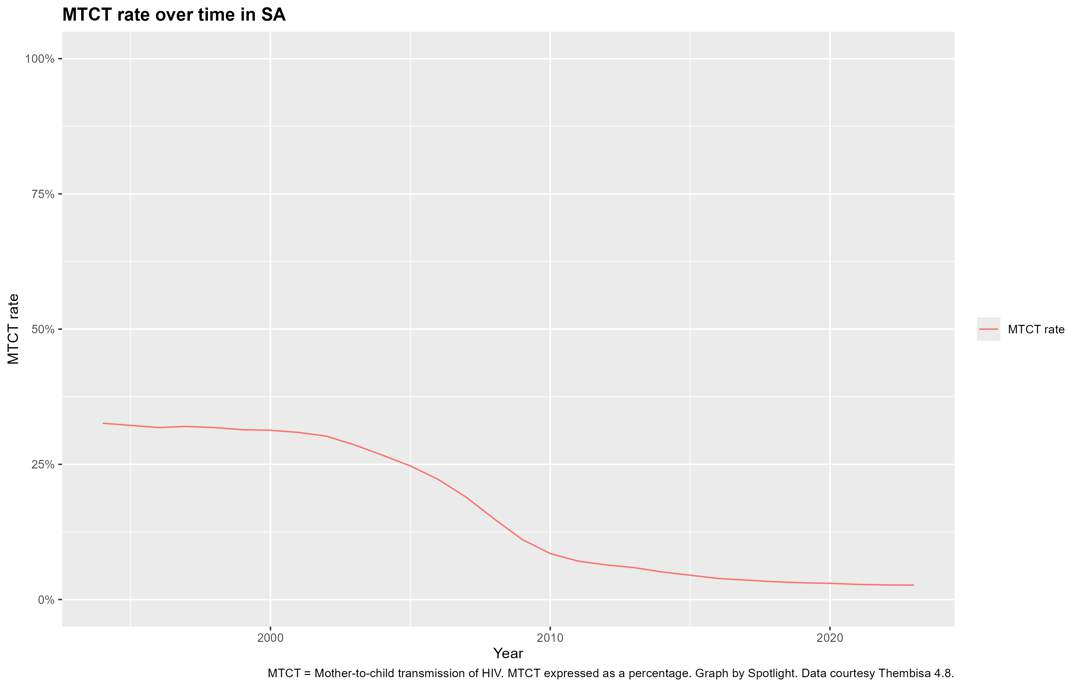

It may come as a surprise to some that,even in the mid-2020s,we still have around 7 000 new HIV-positive babies every year in South Africa.

Things have improved massively since two decades ago when the number was more than 10 times higher,but it is worrying that we haven’t been able to get it closer to zero.

In fact,progress has slowed in recent years.

The dynamics here are not obvious. Most pregnant women in South Africa attend antenatal visits where they are routinely offered HIV testing.

ADVERTISEMENT

If the mother tests positive,she is immediately put on antiretroviral treatment that can suppress the virus and protect both her and the baby.

READ | Aids programmes grind to a halt as government drags its feet

Because of such HIV testing in the antenatal period,we have seen dramatically fewer vertical (mother-to-child) transmissions at or during birth.

Instead,an increasing proportion of vertical transmissions happen in cases where the mother only contracts HIV in the months after birth and then transmits the virus to her baby during breastfeeding,all before she herself has been diagnosed.

Since a person’s HIV viral load spikes very high in the first weeks after infection,this can happen very quickly.

Apart from ongoing vertical transmissions,another point of concern is the estimate that one in three children living with HIV are not taking antiretroviral treatment. (We have unpacked the dynamics behind this in a previous article.)

What is to be done?

In a study conducted in KwaZulu-Natal a few years ago,researchers found that people with HIV who only visited the clinic once a year did as well as people who visited the clinic every six months.

The nurses at the facilities involved were however convinced that the 12-month group would be worse off – if it was up to them everyone would have to come every six months. Well-intentioned as these nurses were,doing it their way would mean more work for them and more clinic visits and more waiting in line for their clients.

Of course,for those people who are ill or struggling,there must be the option of much more regular visits.

But for those who are stable on treatment and doing well,we should at most be asking them to visit the clinic once a year and pick up medicines somewhere convenient every six months.

ALSO READ | Are children living with HIV being left behind? What the stats tell us

South Africa has made tremendous progress against HIV. Yet,as we have shown in this Spotlight special briefing,there are gaps,most notably the fact that one in five people living with the virus are not on treatment.

Getting that fifth person on to treatment,might require us doing things differently than before.

Quite simply,we need to make it easier and more convenient for people to start and stay on treatment.

We have already made several of the right moves. Condom distribution has mostly been a success,it is easy to get an HIV test,allowing nurses to get people started on treatment without the involvement of doctors has worked well,and giving people the option of collecting their ARVs at pick-up points such as private pharmacies has made many people’s lives easier.

ALSO READ | Francois Venter: Our HIV programme is collapsing and government is nowhere to be seen

Though it’s come a long way,the medicines distribution system still falls short of providing everyone with a convenient option for collecting their medicines near their home or workplace.

Too often people still get only enough tablets for a month or two at a time.

For those not keen on visiting clinics,getting an ARV prescription straight from a pharmacy is unfortunately not yet an option. Many people still feel disrespected by the health system meant to support them.

Over the last two decades,we have rightfully been somewhat fixated with numbers like treatment coverage.

One might argue that to scale up treatment as quickly as we did,we couldn’t afford for care to be as personalised as we’d like.

But with the world’s largest treatment programme in place and a mature epidemic,the context has changed.

It is clear where the remaining gaps are – closing those gaps will require that government gets serious about making the health system much,much more friendly to those it is meant to support.

*You can find the complete version of this #InTheSpotlight special briefing as a single page on the Spotlight website.

Note: All of the above graphs are based on outputs from version 4.8 of the Thembisa model published in March 2025. We thank the Thembisa team for sharing their outputs so freely. Graphs were produced by Spotlight using the R package ggplot2. You are free to reuse and republish the graphs. For ease of use,you can download them as a Microsoft PowerPoint slide deck.

Technical note: The Thembisa model outputs include both stock and flow variables. This is why we have at some places written 2024 (for stock variables) and 2023/2024 (for flow variables). 2024 should be read as mid-2024. 2023/2024 should be read as the period from mid-2023 to mid-2024.

Reviewed by Dr Leigh Johnson. Spotlight takes sole responsibility for any errors.

*This article was first published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest. Sign up to the Spotlight newsletter.

United News - unews.co.za